Six years on, London 2012 has almost no legacy and cities are lining up to reject the Olympic movement, so where did it all go wrong?

Julian Cheyne says the 6th July 2005 was one of the worst days of his life.

While Kelly Holmes and Chris Hoy celebrated in Trafalgar Square as the International Olympic Committee announced the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games would come to London, barely six miles away on the Clays Lane estate Cheyne started to realise what that would mean for him.

Before 2005 he was largely apathetic to the Olympics and, convinced that Paris would win the bid anyway, thought the speculation would amount to nothing. But on the 6th July it became real. He’d later be evicted from his home to make room for the Olympic park and see the area he had lived for his whole life fundamentally change.

On Tuesday residents in Calgary went to the polls to reject the idea of hosting the Winter Olympics in 2026. The city joins Rome, Hamburg, Oslo and Budapest in turning down the Olympics after referendums, while other cities such as Boston have seen proposals also collapse without public support.

So why have cities become reluctant to host the Olympics since London 2012, which were supposed to be the best Games in history?

It only takes a visit to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park to start to realise. The park now largely stands empty; a couple of cyclists stop at a Heineken-branded cafe, a scooter rental service hosts a trial and some school children cut across on their way home but, despite the constant reminders of the glory that took place six years ago, the park feels manufactured and cold.

Even around the park’s landmarks, there are few visitors (Credit: Matthew Smith)

If you were to believe the London Legacy Development Committee (LLDC) then the Games would benefit local people and businesses, but beside the Aquatics Centre and multi-purpose Copper Box, there is legacy to show.

And while Stratford is being transformed, much of the area’s regeneration was already underway before the city won the Olympic bid. Despite the proximity and much of the publicity about legacy, Stratford City (including the Westfield shopping centre and new residential blocks) was never intended to be part of the Olympic plan.

It’s a point that Cheyne is keen to make when I speak to him about the legacy of London 2012. Cheyne’s experience with organisers led him to join GamesMonitor, a site that aims to ‘debunk Olympic myths’ – a site he still maintains six years after the games.

He tells Voice of London that the organisers, “were lying from day one” by suggesting the area was a wasteland before the Olympic bid, and a lack of scrutiny meant lying became “endemic to the project.”

He argued that while the Stratford City project started to redevelop the area, the Olympics were “completely destructive”. Cheyne says; “You have an enormous regeneration project already underway, and the Olympics were wiping out a valuable industrial sector right next door. The loss of jobs and the destruction of local industry has meant that all the other industrial areas in nearby Hackney Wick and Fish Island are also being decimated.”

This has led to a shift in the development path that is happening in Stratford, as industry had to leave the area, those jobs left as well. One company said at the time that during the redevelopment period of Stratford they would have expanded while also including much-needed housing as part of their project – that was scuppered by the plans for the Olympic Park.

That lack of industry has also contributed to a process of replacement within the area’s population. While those jobs in ‘dirty industry’ were often taken by local people, they are being replaced with jobs from arts and media bodies such as the BBC and V&A, who will move into the Olympic Park in 2021. Cheyne fears that the introduction of these elite arts bodies into Newham will continue to transform the area beyond what the local residents need or want.

Newham currently has one of the highest rates of income poverty, unemployment and homelessness in the capital, and little of these plans will help alleviate these problems. The East Bank project will come with a cost of at least £151 million of further government funding.

Developers argue though that these institutions are well placed to make careers in the arts and media more accessible for local residents. The jobs produced as a result of these schemes will also generate income and spending for the area, potentially leading to more lasting results.

Some of the park’s artwork is more appreciated than others. (Credit: Matthew Smith)

Nothing highlights the difference between the new and old in the area as well as the Stratford Centre. In the shadow of the glitzy Westfield, the older shopping centre has become a makeshift homeless shelter.

The Newham Recorder reports that two rough sleepers have died in the centre this year, despite charity workers often being on hand. The newspaper says up to 50 people sleep in side the complex every night, and authorities have struggled to control the use of spice and other recreational drugs.

Cheyne, who has been in contact with other anti-Olympic groups, tells me that London 2012 has proved to be “damaging to the whole Olympic movement”. The academic Andrew Zimbalist, who wrote a book on Boston’s opposition to the Games, has repeatedly cited London as an example of how hosting the Olympics has few real benefits. London has experienced no increase in tourism, and no real sporting benefits – even during the Olympic period in July 2012, New York (whose bid lost out in 2005) had more visitors than London.

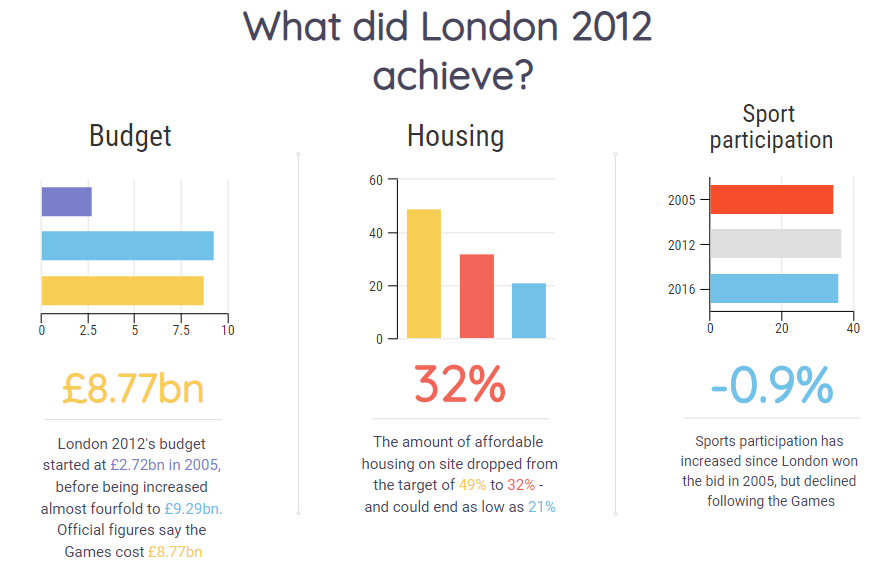

The sporting legacy is also up for debate. Sporting governing bodies point to the rise in participation from 15.2 million people a week when the bid was won in 2005, to 15.5 million in 2015 (with a peak of 15.9 million in 2012). There has also been a significant increase in Olympic success, from just one gold medal in Atlanta in 1996 to 27 in Rio 2016, the best ever result at a foreign games. This suggests that there has been a new and successful focus on progressing athletes to the elite level, and the benefits from success at that level may take another decade to fully understand.

It seems inevitable that hosts of the Olympics will suffer the same struggles as London has; “to win the bid you have to promise the earth and it’s undeliverable” He mentions that the original budget for the Games was under £3billion, although now organisers say that it cost almost three times that. Other estimates believes that the total costs is probably greater than that, potentially over £12billion.

It should be noted though that London’s struggles have been minor compared to other recent games, especially Athens 2004, where many venues stand empty and decrepit – this was through a smart plan of using temporary stadiums in both the park and around the country, for sports such as hockey, basketball and beach volleyball, that wouldn’t need large venues once the Games had finished.

Credit: Voice of London

Benedetta Laterza lived in Turin during the 2006 Winter Olympics, and she remembers the excitement being shortlived. Just as in London, there was no benefit to tourism and “many of the skiing sites have become abandoned in the past 10 years.”

Rome is one of the cities to abandon recent Olympic bids and Laterza says “Italy is sceptical about bidding again because they think it’s just a waste of public money.”

And problems with the London Stadium especially mean that Londoners’ money will help to subsidise a Premier League side, as well as the park, the foreseeable future. That’s despite West Ham United being valued at over £200 million.

The empty park also shows that the promised wave of jobs just never arrived, recent estimates show that less than a quarter of the promised jobs have materialised, while other estimates suggest the Olympics is responsible for actually taking 4,000 jobs from the area.

Three quarters of the 11,000 jobs promised to replace those lost as a result of the creation of the Olympic park still don’t exist. Because like everything else associated with the London 2012 legacy, it was a lie.

An £8.7 billion lie https://t.co/dX5005Y5K8

— 𝙆𝙀𝙑𝙄𝙉 𝘽𝙇𝙊𝙒𝙀 🏴 (@copwatcher) October 25, 2018

When asked if there is any kind of legacy to show for London 2012, Cheyne concludes “there was never any chance that London was going to deliver a 10th of what it promised. It has delivered virtually nothing, but it’s done a lot of damage.”

Cheyne argues on GamesMonitor that London 2012 never left a legacy, but it did leave an aftermath. It’s no surprise that other cities have started to take note.

Words: Matthew Smith | Subbing: Charlie Bradley