Underneath Nelson’s Column, sirens scream and wheels screech, boots clomp and hooves clop as hundreds of police assemble. A news van rolls in and a made-up reporter emerges from the passenger side while the rest of the team launch camera, light and audio equipment out the rear doors and onto the concrete.

A lorry stops dead on the A4 at the base of the monument.

Pop-up stalls erect and campaigners emerge engaging with the newly-formed crowd, encouraging them to take one of the thousands of leaflets, to carry one of the thousands of placards, to march with them – as one of the thousands.

The lorry becomes a thundering stage having shed its curtains. Activists shout down microphones and their words echo above the clamorous crowd below.

A series of banners, each five or so people long, unfurl across the ones fronting the march and they aim the procession down a near-empty road flanked by metal barriers and glowing police officers.

From Trafalgar Square, protesters will march for just under a mile.

Just under a mile away, Donald Trump is attending a dinner at Buckingham Palace.

Nurses and doctors are leading this rally, ordering President Trump to keep his “hands off our NHS”.

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

On November 20, 1887, a 41-year-old man was knocked over by a horse, subsequently trodden on, and later died from his injuries. The horse was part of a mounted police unit (patrolling a demonstration at Trafalgar Square). The man was Alfred Linnell. He had made a living printing documents before attending a demonstration against police violence.

Linnell’s name doesn’t resonate like the Conan Doyle or Darwin of his day and his tragedy may not be taught in schools. But since his death, he’s become somewhat a historical legend. His name rests on display at the Museum of London, a pamphlet, in honour of his passing and composed by prestigious Victorian artist and poet William Morris, who unambiguously titled the piece: ‘A Death Song’. Linnell’s fatal injury – a hefty hoof to the hip, no matter how unfortunate, happened to be at the right time and the right place in history. For Linnell, he went from hapless bystander to revered martyr; the name people would shout at the protests that followed.

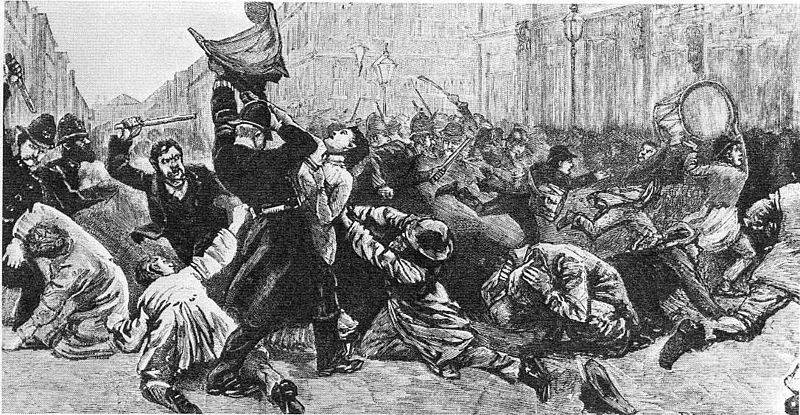

Exactly a week before Linnell’s death is marked as Bloody Sunday: a vicious protest turned brawl between police and demonstrators at Trafalgar Square. (Not to be misconstrued with the events of 1972 in Northern Ireland, or any other – and rather alarmingly, there’s a few – Sundays remembered with that same tag.)

Placards held aloft, 10,000 demonstrators – comprised of Socialists, Radicals and Unionists – departed in factions from different locations throughout the capital. All marching towards the same objective: Trafalgar Square. Expecting the rendezvous, 2000 police officers and 400 troops. Armed and regimented, they stood waiting at the Square.

What followed was chaos: 400 arrested. 75 seriously injured. Two policemen stabbed. One protester bayoneted. Police: one; protesters: nil.

They’d been protesting unemployment and coercion in Ireland. However, the reason behind the chaos was far more deep-rooted.

The week before Bloody Sunday, the chief of the Metropolitan Police banned public gatherings in Trafalgar Square, declaring it property of the Crown. The chief of police was Sir Charles Warren, remembered most for failing to catch one of London’s most infamous criminals, Jack the Ripper. And, for bearing a face that consisted of mostly a moustache.

Since cutting the ribbon on the public space in the spring of 1844, the Square – commemorating a British naval victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, in which Admiral Nelson died – had become a place for public demonstration – particularly for the unemployed. By the late 1880s, the unemployed were filling the square daily. Hundreds were sleeping there at night and bathing in the fountains. The complaints from the government had started to amount on top of the already complaining local businesses. And so, Sir Warren, wailing the words through his wavy, weighty whiskers, ordered his men to clear them from the Square.

The eviction enraged the people camped at the square because they felt their rights had been breached. Words started to spread fast they would return to Trafalgar Square, in numbers and solidarity, to exercise their right to free speech. But perhaps, the word spread too far…

The response: Bloody Sunday. People expressed their right to free speech in the face of injustice; despite being met by the overwhelming face of armed forces. What happened cemented Trafalgar Square as the place for protest in the capital, not just in the weeks that followed, where Alfred Linnell’s death, however accidental, had become engrossed in the movement, but to this day.

One newspaper’s recollection of Bloody Sunday. Pic; Public Domain

Underneath Nelson’s Column, orange and blue flags flop and occasionally they ruffle when a soft breeze drifts through, stressing the flags just enough to reveal their triangular shape and Khandas.

Thousands of Sikhs, chiefly clad in the same orange and blue of the flags, stand in the sunken section of the Square and sit on every space the wide-stretching stairs can offer, filling any gap from the four bronze lions to the front doors of the National Gallery, brimming and spilling life onto the roads of the City of Westminster.

It is a summery day in June and Sikhs from all over the UK and Europe gather at Trafalgar Square in remembrance. From a temporary stage where speeches are being given, three words resonate. Truth. Justice. Freedom.

Unified in faith and the vivid colours traditionally worn for commemorative occasions, they remember those who lost their lives in the 1984 Sikh Massacre.

Sikhs – which makes up one percent of London, and less that one percent of the entire United Kingdom – congregate in honour of their belief at Trafalgar Square. Trafalgar Square provides a public space for representation throughout the country.

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

- Dan Branston

April 23, 1913. Women’s Social and Political Union cause a stir at Nelson’s Column. 3000 people attend and three are arrested. They protest the oppression of the Suffragette. And again, on May 4 with the Free Speech Defence Committee. Footage below, provided by the BFI, depicts Sylvia Pankhurst – a campaigner of the Suffragette movement, during the ‘Trafalgar Square Riot’ of 1913.

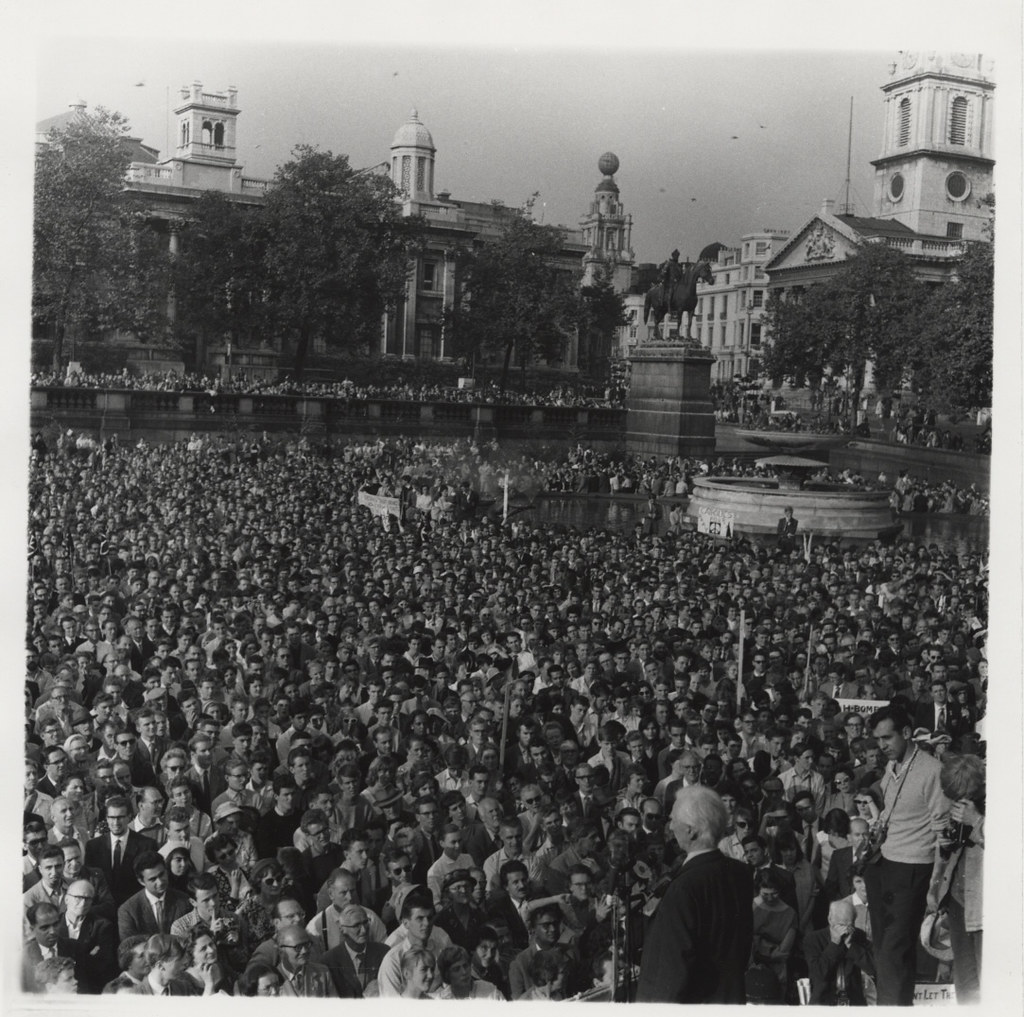

Easter Sunday, 1958. Protesters march from Trafalgar Square to Aldermaston. Aldermaston is a quaint village in West Berkshire and is synonymous the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), the site that is responsible for the manufacturing of the UK’s nuclear warheads. Protesters march for four days covering over 50 miles. Repeating the march annually and reversing the route, by 1961 they attracted over 160,000 marching towards the Square.

Aldermaston March rally at Trafalgar Square for its second year (1959) Pic; Robert Joyce papers

March 31, 1990. 100,000 people gather at Trafalgar Square to protest Poll Tax, (a replacement to rates implemented by a Tory government). The result: 400 arrests and £400,000 damage to property. The outrage has been a recognised chapter in the downfall of Margret Thatcher, who stepped down seven months later.

Scenes turn violent at the Square over Poll Tax (1990). Pic; James Bourne

June 1996. 66 injuries and 200 arrests after England were knocked out by Germany in the World Cup. 2,000 intoxicated fans spark a riot and take over the Square. Since 2001. Now attracting 35,000 each year, Diwali’s – the Hindu festival of light – biggest gathering in the city happens annually at Trafalgar Square. November 2003. 100,000 demonstrators meet at Trafalgar Square against President Bush and his decision to invade Iraq; it’s the largest mid-week protest in London at the time. Since 2004. Trafalgar Square becomes a hub for Pride London every June – standing for the equality for LGBTQ+ community. Last year over a million people attended. November 2010. Students protest tuition fees and cuts to education at the Square. Police deploy kettling tactic, stopping them from marching and holding them in one place. April 2012. Disabled protesters chain themselves to lights at the Square protesting austerity measures. November 2015. The fountains at Trafalgar Square are died red by feminist activists during a protest about budget cuts to domestic abuse services. 2016 – ongoing. Brexit. The days after the result, thousands gather at the Square in support of both sides. March 2017. Thousands pay tribute at Trafalgar Square during a vigil for those who lost their life in the Westminster terror attack.

To list everything that’s happened there, even in a year, would be immensely taxing – it’s the sort of place that has something going on daily. (As I write this people lay on the concrete in the Square in the pouring rain and freezing cold night as part of The World’s Sleep Out: to raise awareness of homelessness.) But as the noted dates above suggest, Trafalgar Square is a place that can write its own history, and sits in the heart of London, representing the city, country and world.

Underneath Nelson’s column, the scattered tents look slack and weather-beaten from the rain. Ridge tents, dome tents, tunnel tents and pop-up tents, strewn amongst the puddled floor.

There are songs and chants coming from a range of instruments and voices. There are people prodding hourglass stickers no larger than a button onto the raincoats and bags of tourists and commuters and whoever happens to be walking by, welcoming them to a free hot meal set up in one of the bigger tents that appears more like a stall you’d come across at Glastonbury Festival.

Extinction Rebellion (XR) – protesting the government’s inaction on Climate Change – have turned Trafalgar Square into their base.

October 7, 2019. XR had scheduled a fortnight of peaceful protests from 7 to 19 October. From the Square, they would orchestrate demonstrations across the centre of the capital, targeting everything from London’s airports to the Bank of England.

Thousands of XR supporters claiming territory at Trafalgar Square. Pic; Joseph Brett

Flights were delayed when a plane and a terminal building were scaled at City’s airport. At the Palace of Westminster, the Elizabeth Tower was scaled by a Boris Johnson impersonator. Some routes on London’s integral tube service were halted for a short while and major roads – including the roundabout abutting Trafalgar Square, that had become an overflow campsite at the time – were blocked. There was so much sticking their hands to the walls and windows and the revolving doors of cooperate buildings and banks and media institutions you’d of thought Gorilla Glue might’ve sponsored the mass-protest. Gallons of red paint were used to drench hands, pavements and roads to represent death triggered by climate-related disease and disaster.

But these were just a few of the measures taken by XR that caused a tremendous wave of disruption through the capital. And it is understandable why it didn’t take long until Londoners became angered, especially while disrupting the underground – a service that carries 2 million people daily; whether they believed in the cause or not, people could no longer get to work to earn money and get to hospitals to receive treatment.

Police had arrested 1,400 protesters during the first week. The ‘Autumn Uprising’ – XR’s self-titled fortnight procession – had amassed a bill of £21m for the Met Police, £6m more than they’d normal spend yearly on the violent crime taskforce – a unit dedicated to reducing knife crime.

October 14, 2019. As part of a blanket ban on protests across the city, police implement section 14 of the Public Order Act 1986. Police forcibly remove Extinction Rebellion protestors from Trafalgar Square that evening. The eco-protesters are just over halfway through their scheduled demonstration, they still have five more days to go.

I’m sure when Sir Warren had instructed officers to oust the unemployed from Trafalgar Square the week before Bloody Sunday, it unfolded fittingly given the period: a bunch of bobbies bullying the demonstrators away with truncheons. And that couldn’t be further away from the clearing of XR over 100 years later, and besides, XR were conducting a peaceful protest. Yes, police arrived in large numbers, surrounding the Square with vehicles, but they had a long night ahead of them. The peaceful nature of the protest meant there’s no resistance, but it didn’t mean they would freely move from the Square. Well, not without assistance. Anyone that wouldn’t budge under police orders were scooped up, usually three officers per protester, and carried from the Square into the back of a van to be carted away. But history does repeat itself because the unemployed protesters removed from Trafalgar Square in 1887 and the XR activists evicted a few months ago both believed their right to free speech had been infringed.

Police line the Square ready to clear XR protesters out of Trafalgar Square. Pic; John Paul Brown

XR had – according to a Met superintendent – become a major disruption and was feared it would become worse. That is why they were cleared from Trafalgar Square. That is why the 1986 Public Order Act was issued. If a group – two or more people – assemble in connection with the ‘Autumn Uprising’ inside London, that would be illegal.

Two days after the ban and placards held aloft, XR protesters piled into the Square. Of course, they are still protesting the government’s inaction on Climate Change, as the unemployed protesters were still protesting unemployment on Bloody Sunday, but what had got them so rallied is exercising their right of expression. Protesters gathered having slapped a strip of black tape over their mouths to represent the Met Police silencing them. What happened wasn’t another Bloody Sunday – nonetheless, it was Wednesday – when the police arrived at the Square. Repeating the same method as two days previous, police scooped up protesters and removed them by hand, enforcing the ban.

Things go a step further, XR filed a lawsuit against the Met Police after being removed from Trafalgar Square – the second time – insisting their actions were unlawful. It was no longer just about Climate Change; it was about the same thing the name Arthur Linnell has become to mean since he stumbled in front of the horse that fateful day: the right to freedom of speech. And unlike Linnell, we’re fortunate enough to be at a certain time, and have certain rights, that when we march underneath Nelson’s Column, they prevail. Even if it takes a little time…

November 16, 2019. High Court rules the police ban on Extinction Rebellion unlawful.

Words Dan Branston