We live in a world where our personal information is not our own anymore. Just from apps, companies know where we are at this moment. Even stores offering free wifi in exchange for your email and social media details gain access to customers shopping habits.

“Data is the new currency” is the motto echoed in the tech industry. Data allows sites to enhance customer service, reframe marketing strategies and profit for data brokers. But what these companies know about their consumers is more than what the consumers would like strangers to know about them.

It goes beyond names and email addresses. According to the Federal Trade Commission, data brokers have a vast tract of data about your home, money, health, and more:

- The home you live in and how many years you’ve lived there

- The credit cards you have and your credit score

- Bankruptcies and criminal charges

- If you’re married or pregnant

- Even height and weight

Yet, few seem to see to the moral and ethical dilemma of privacy being taken and monetised. Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, called the practice “surveillance” and railed against the ‘weaponisation’ of personal data with “military efficiency” in a speech made at the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners in Brussels.

The data debate intensified earlier this year when Facebook sold users’ data to the political firm Cambridge Analytica. A line was crossed and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) changed the way businesses gather and handle consumer details within the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA).

GDPR gives consumers the right to know the data companies have about them and obligates businesses to have better data management. It enforces penalties such as fines to business found guilty of data misuse. It explains why when you visit almost any major website, a message pops up outlining the use of cookies, why they use them, and asking for your consent to use them.

There is an option to see the detailed use of cookie but not to decline the use of cookie. If you refuse, it’s not guaranteed you can view the article. So, what do people in this scenario? Is the process increasingly resembling a monetary transaction, except this time you’re giving away personal information in exchange of getting access to content?

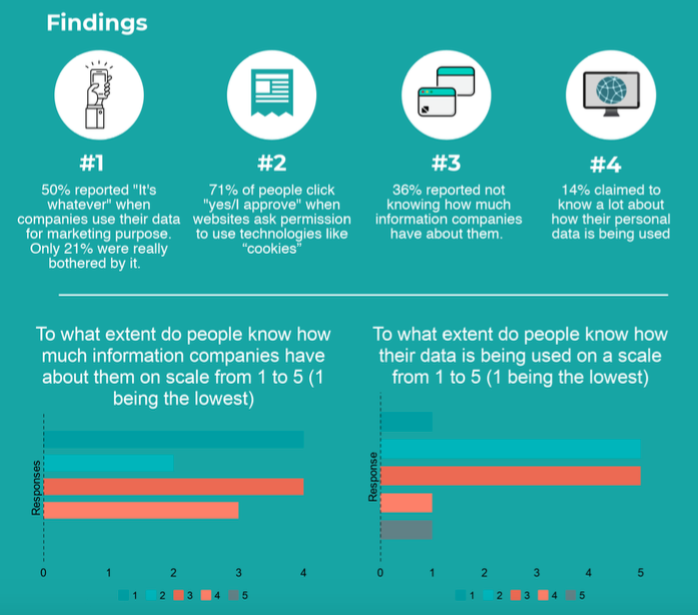

Voice of London got to the bottom of this with a questionnaire. The questionnaire, done both online and in-person, collected people’s opinion and attitude about the practice of collecting personal information about users.

The results show people don’t seem to mind companies knowing where and how they live. People have become accustomed to being monitored and there’s nothing they can do about it.

Cook backs the tough privacy laws in both Europe and the U.S. and he listed the measures both companies and customers should take to combat misuse of personal data in a series of tweets.

Second, users should always know what data is being collected from them and what it’s being collected for. This is the only way to empower users to decide what collection is legitimate and what isn’t. Anything less is a sham.

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) October 24, 2018

Third, companies should recognize that data belongs to users and we should make it easy for people to get a copy of their personal data, as well as correct and delete it.

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) October 24, 2018

And fourth, everyone has a right to the security of their data. Security is at the heart of all data privacy and privacy rights.

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) October 24, 2018

This is a feature of the 21st century. We’re stuck in revolving glass door of protecting but no possible way of avoiding technology in our everyday life.

Words by Earyel Bowleg | Subbing by Maria Campuzano