Health, be it physical or mental, is fundamental to one’s well-being. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, adapting to the ”new normal” has impacted the daily lives of the youth and how they perceive their future.

According to the Department for Education, access to NHS mental health services has been maintained for the younger generation. Although referrals to these services were lower during the early stages of the pandemic lockdown, an increase was seen during June as restrictions were eased.

The British Journal of Psychiatry surveyed 3,000 adults in the UK this year (March – May) and found that suicidal thoughts increased from 8% to 10%. The highest increase was witnessed among young adults aged 18-29, rising from 12.5% to 14%.

A frontline medic told The Voice of London that the ongoing social changes, as a result of the pandemic, had a ”profound impact” on the mental health of many, with ”heightened levels of anxiety and uncertainty” affecting day-to-day lives.

“The on-going social changes have had a profound impact on the mental health of many. The pandemic has definitely heightened levels of anxiety and uncertainty – which must be catered to by the government and healthcare professionals” — Frontline medic at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, King’s Lynn

In October, the Department of Health and Social Care in England announced that it was increasing investment in mental health services.

Most recently, the government issued a report on the state of young people’s well-being in England this year and noted that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant changes to their lives. The data, collected between March and September, indicates how young people have felt in terms of their anxiety levels.

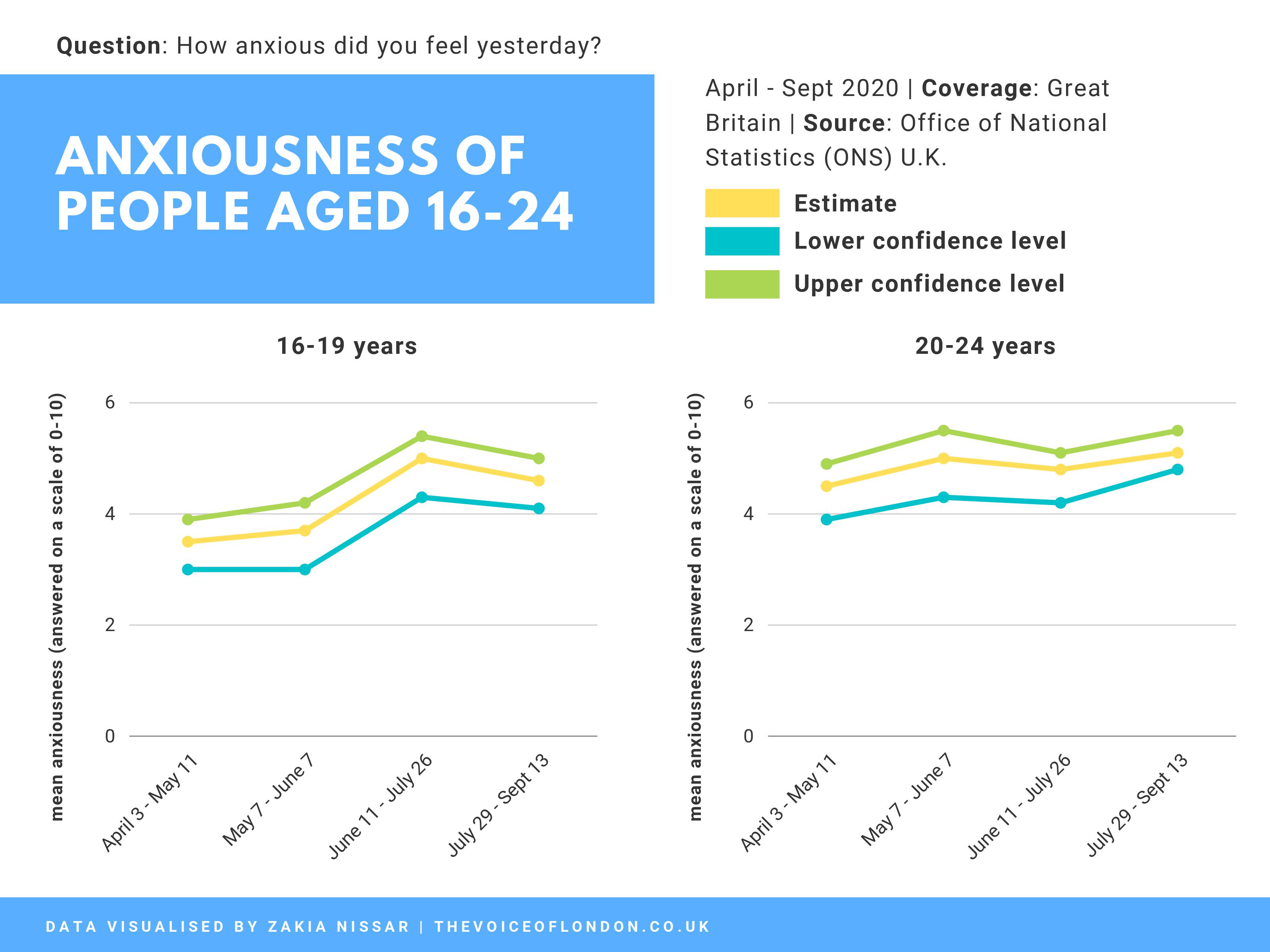

Anxiousness of young people aged 16 to 24:

The Office for National Statistics found that during early April, people aged 16 to 19 on average rated their anxiousness as 3.4 (out of 10), whereas those aged 20 to 24 rated higher, scoring 4.3 (out of 10). Between June and July, people aged 16 to 19 rated their anxiousness at a higher average of 5 (out of 10). In the last bracket of data collected, 16 to 19 year olds reported an average of 4.6 (out of 10). Overall, unlike people between 20 and 24, anxiousness reported by those aged 16 to 19 rose between April and September 2020.

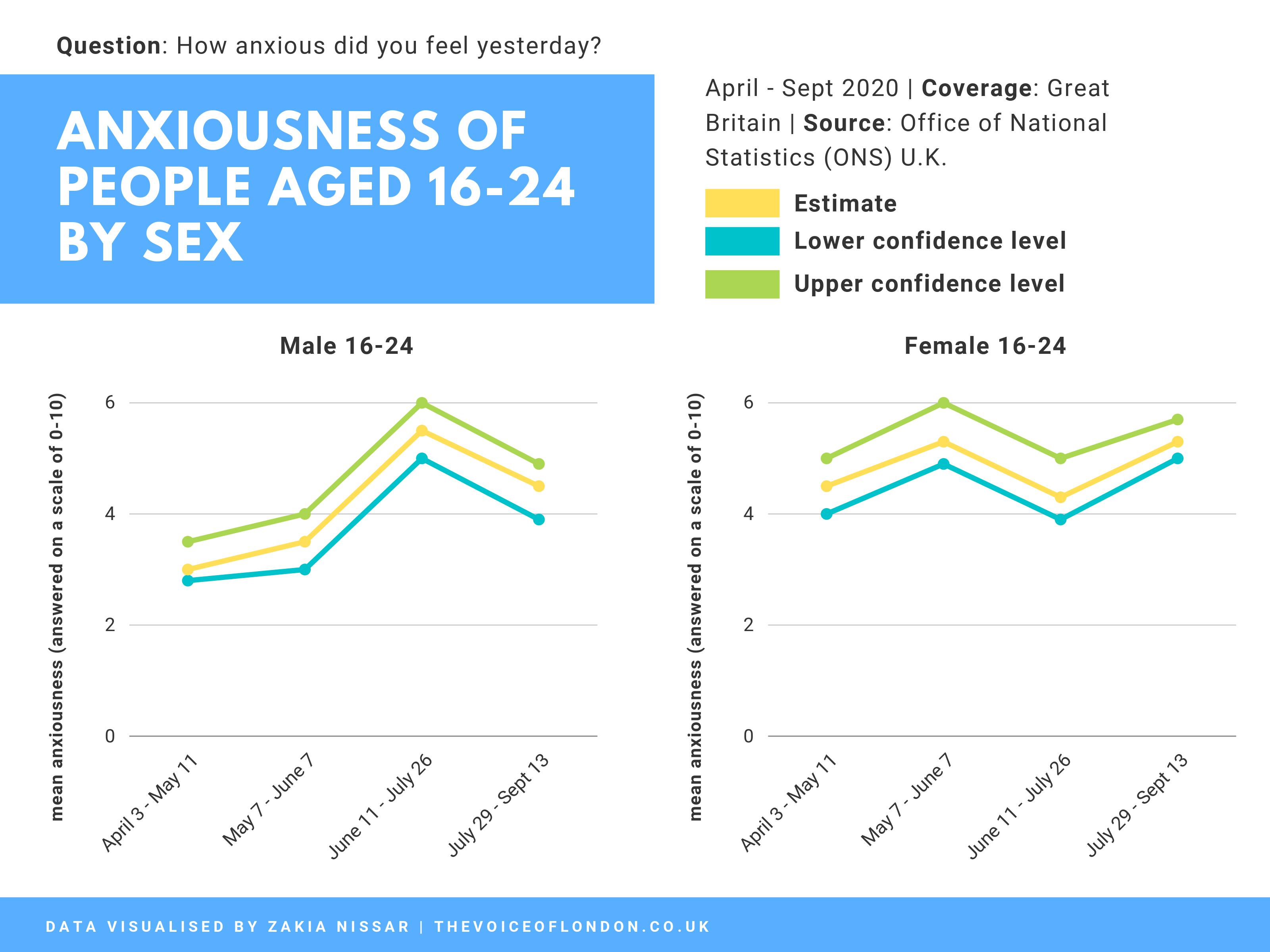

Between April and May, women aged 16 to 24 displayed a higher average of anxiousness (4.6) than young men (3.1). However, this consistency did not follow over summer, as young men reported more anxiousness than young women during June and July. By ending July to mid-September, anxiousness increased within young women, whereas young men witnessed a drop in levels compared to the spike in mid-June to late July.

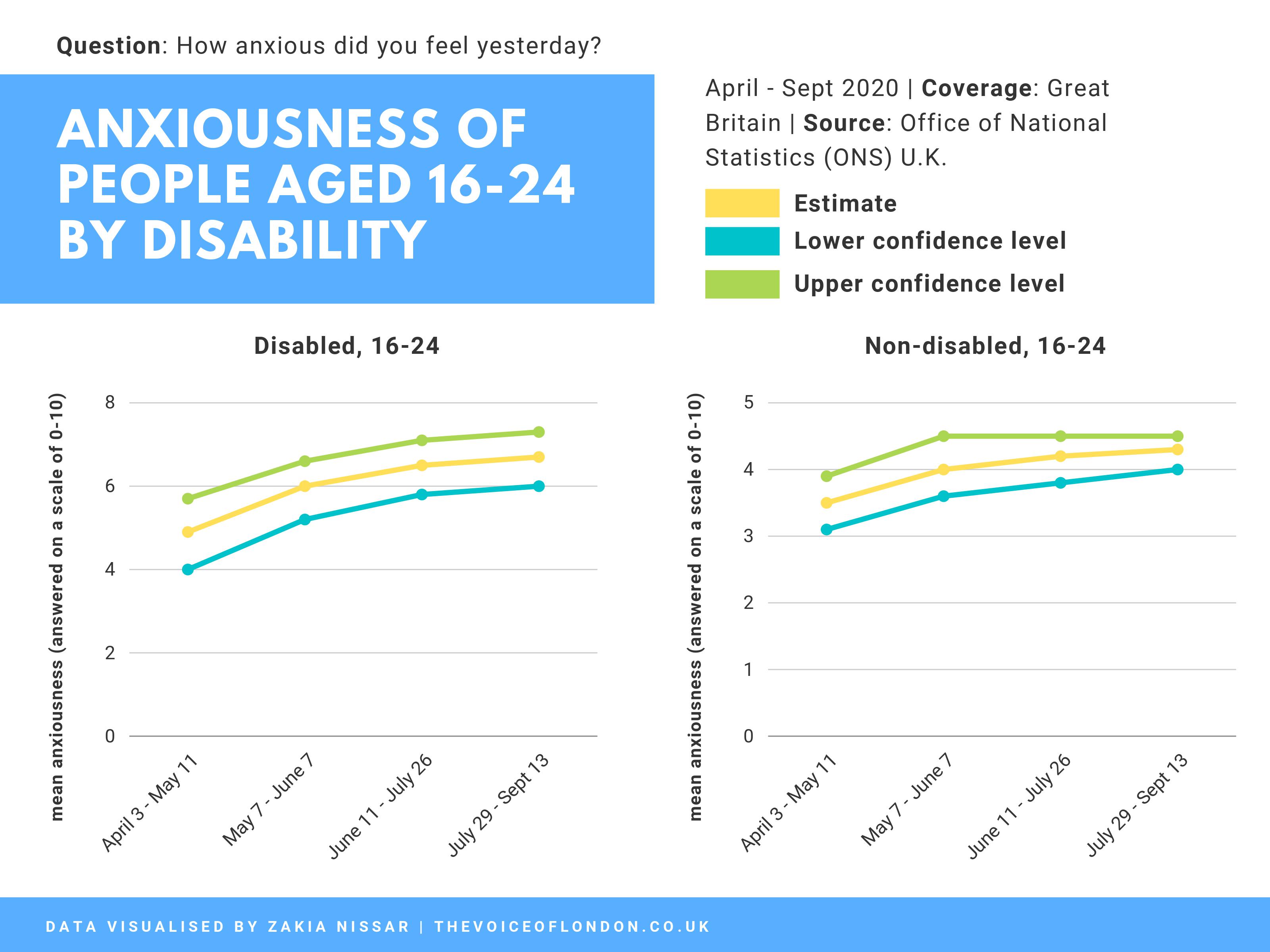

As per the Office of National Statistics (ONS), disabled young people aged 16 to 24 rated their anxiousness on average as 4.8 out of 10 between April and May. On the other hand, non-disabled people reported a lower average of anxiousness in the same months, at 3.6 out of 10. Over the following months, anxiousness by disabled young people witnessed an increase. By late July to mid-September, the average levels of anxiousness by disabled young people scored at 6.6 out 10, compared to the significantly lower levels among non-disabled young people (4.3 out of 10).

Research by the London Assembly‘s health committee indicated that the prevalence of mental ill-health is higher among marginalised groups in the city and that there can be physical barriers to accessing mental health services. It indicated that the mental health needs of the marginalised are often overlooked by existing health and well-being strategies.

Student profiles and how the pandemic has impacted their mental health:

Since returning to the U.K. to continue her studies, 22-year-old Warshma Chughtai from Karachi, Pakistan has dealt with pandemic anxiety by calling her loved ones every day.

Dina Nazari, 20, noted how the lockdown has affected her lifestyle in ways such as changing eating habits and feeling constantly demotivated.

Maria, 19, re-iterated the increasing lack of motivation and restlessness felt from being unable to socialise due to the pandemic.

What’s next?

As the pandemic’s winter months emerge, research from The Weather Channel and YouGov noted that 29% of British adults experience symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) during this time of the year. Fifty-seven per cent (57%) of adults reported that their overall mood is worse during the winter season in comparison to the summer. As well as this, women are 40% more likely to experience symptoms of SAD, which is sometimes referred to as ”winter depression.”

These figures — which are twice as high as previous estimates — aim to push businesses and the NHS towards introducing strategies to deal with the impact on public health amid the pandemic.

As the pandemic advances alongside the harsher season, the government is under scrutiny to prompt appropriate responses to prevent a mental health crisis. Their ability to consider the needs of the marginalisedand subsidise the mental health infrastructure will undoubtedly be taken into account by the public.

For information on how to protect your mental health, visit the NHS web page to access the range of mental health charities and organisations.